Scholarship

My most recent writings revolve around the impact Deep Listening® has had on my performance practice, teaching, and composing. I write, give talks, and produce events that illuminate my research on developing restorative creative practices in collaboration with other trauma-informed artists and therapists. Stay tuned for more information about my soon-to-be-published works.

The Existential Crisis and self-discoveries around the concept of the Expanded Instrument System

November 25, 2019

Around the early ’90s Pauline Oliveros and David Gamper (along with other notable musicians since then) developed the Expanded Instrument System (EIS) to broaden the musical palette for interaction between players and electronic instruments. To design a flexible musical system that allows a musician to improvise requires an active imagination, deep knowledge of the tools at hand and a willingness to question…one has to constantly be able to modify one’s perspectives and learn about all the ways music and sound works, as well as how people interact with each other and machines. When I was recently asked to give a presentation at the University College Cork’s Master’s (of Experimental Sound) students class “Expanded Instruments Systems” I was not prepared for the barely-lurking-under-the-surface existential crisis that was about to unfold. I asked myself, “how does my work relate to the concepts around the Expanded Instrument System? How is my work expanding or extending the tradition of the flute? Does it have to be only with electronic systems? Can expanded instrumental systems apply to acoustic systems and approaches?” As I prepared for my presentation of my work as a flautist, I began to look farther back… 27 years…to the beginning of when I first started to embark on “extended techniques” during my Master’s at UCSD.

Up until recently, I wasn’t bothered by the term “extended techniques”. It made sense because most of the music that utilizes “new” techniques began to appear in the later half of 20th Century. Many techniques such as multiphonics (two or more pitches played simultaneously), key clicks, singing-while-playing, air sounds, were outside or “extended” from the Western-European orchestral traditional methods of playing the flute. While writing my Master’s thesis and Ph.D. dissertation in the mid-90s, I learned that most of these techniques actually come from ancient practices, from various musical traditions from around the world. Air passing through tubes have been sounding before there were humans on the planet. People have been singing-through-tubes for millennium. I realized then, that the term “extended techniques” didn’t seem right at all. There is nothing extended about them when, in fact, it is the classical orchestral tradition that has kept our instruments shackled and bound. While I knew this, in theory, it has taken me this long…over 25 years, to realize my own trajectory when it comes to “expanding” the flute or how my work with and without electronics was part of a movement (perhaps more like an extend “stream”) of the Expanded Instrument System.

There is a lot to say about my trajectory between 1992 and today 2019, however, I will save that for another time. Instead, for now, I will jump past my work with developing singing-while-playing, interactive electronics, improvisation, complex repertoire, moving while playing, various articulations, and new piccolo techniques. I’ll just leap over to the present “Ah Ha!” moment of today…

What I learned from my talks with the composers John Godfrey and Karen Power, as well as with the Master students at UCC, is that my life’s work has not been about expanding the flute. Instead, my work has brought me closer and closer to the essence of the flute, to what it does naturally, as a metal tube, with keys. Instead of trying to conquer the instrument, I’m allowing now the instrument to shape me and the music. Instead of trying to dampen the “noise”, I welcome all the sounds, textures, timbres, residual ghosts and sonic tubular mysteries to unfurl. Instead of expanding the instrument, I’m expanding my mind. All this time, I’ve been expanding my relationship to the instrument. Electronics have allowed me to do the same. But both, the flute and electronics are merely tools. They are not my “system.” There is no outer system. The system, my friends, is the patterned, habitual ways of thinking: how do I use the tools at hand? I ask (and have been asking): what if? how can I do this? What about imagining that?

The “system” is finding ways to infinitely probe the boundaries of possibility and potential of myself and the tools I use. That’s my EIS. The system is not necessarily to expand my instrument but to allow it (whatever tools I’m using) to show me it’s essence, it’s voice, it’s way of being. Instead, I’ll continue to invent ways to allow my tools to speak their own language. My work, mukta for solo piccolo unplugged the imagination. My piece within the fata morgana gave me the permission to live within the fragility of sound. Playing with electronics allows me to create dreamscapes of sound that cascade and unfold.

I just have to stand back and listen.

The Vocalization of the Flute

University of California, San Diego Ph.D. Dissertation

1996

This dissertation is divided into three sections each one exploring the musical techniques of singing-while-playing the flute. The first section introduces some of the cultures around the world that incorporate singing-while-playing through a tube (flutes and otherwise). Such cultures as the Ba Benzele and Aka Pygmies from the Central African Republic, the shepherds from Rajasthan, India, the peoples from the Solomon Islands all integrate the voice into their musical playing of the flute or with tubes. The second part is the Manual for how to sing while playing the flute (a term that Jane calls “vocalization”) specifically for flutists of the Western-European flute tradition but may be easily transferred to other flutes and traditions. This “how to” section contains both specific detailed guidelines, as well as original etudes that cover a variety of techniques. This manual is also informative for composers interested in how to notate these techniques. The third section covers the valuable pedagogy of singing-while-playing. While working with her students, an analysis is offered on the benefits for learning this technique.

The second part of the dissertation is “The Vocalization of the Flute, a manual for singing while playing” and is available directly from Jane Rigler (contact her here).

For information on how to obtain this work through international libraries, click here.

January 2025

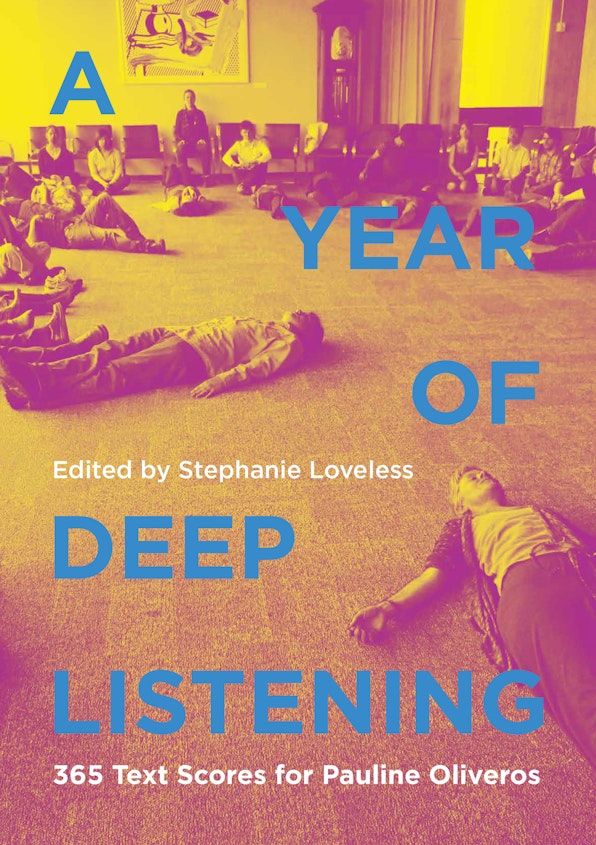

I have co-written with the extraordinary sound artist Maria Chavez the introduction to Chapter VIII “Scores for Listening Beyond Music,” in this newly released book, A Year of Deep Listening: 365 Text Scores for Pauline Oliveros, edited by Stephanie Loveless and distributed by MIT Press. You can get a copy here of this interactive book that invites us all to listening with our ears, to ourselves, our bodies, our dreams, our imaginations, our communities, our lands, our ancestors, our animal and biological friends. Purchase the book and get more information here.